Black Kid Who Pulled His Pant Way Up His Waist Had a Funny Voice Who Was It

Muhammad Ali, the legendary boxer who has died at 74, made us laugh, curse, cheer, and cry. Most important, he made us brave.

1942-2016

By Robert Lipsyte

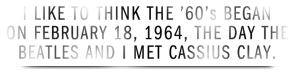

The Beatles were on their first American tour, and they had been taken to the Miami training camp of Sonny Liston, the heavyweight champion of the world, for a photo op. Liston took one look at the four mop-topped Brits in their matching white terry-cloth cabana jackets and refused to pose with "those little sissies." So the photographer scrambled for second best. Stuffing the lads back into the limo, he headed for Clay's training camp, the Fifth Street Gym.

Because The New York Times's boxing writer didn't think the fight between Clay and Liston was worth his time, a kid reporter had been pulled off rewrite and sent instead. Everyone knew Clay had no chance, so my instructions were stark: as soon as I arrived in Miami Beach, I was to drive my rental car between the arena where the fight would be and the nearest hospital until I knew the route cold. The Times didn't want me wasting any deadline time getting lost on the way to the intensive-care unit.

I had the route down by the time I got to Clay's gym. He wasn't there yet, but these four guys my age were, and they were stomping and cursing because security guards had herded them into an empty dressing room to wait. Had I any sense of who they were (or would become), I might have been more reticent in pushing my way into the room too.

I asked for their predictions for the fight. They said that Liston would destroy the silly, over-hyped wanker who had no business fighting for the title. Then they began cursing again and banging on the walls.

Suddenly the dressing room burst open, and Cassius Clay filled the doorway. The Beatles and I gasped. He was so much bigger than he looked in pictures. He was beautiful. He glowed. And he was laughing.

"Hello there, Beatles," he roared. "We oughta do some road shows together. We'll get rich."

The Beatles were quick studies. They followed Clay to the boxing ring like kindergarten kids. You would have thought they'd met before to choreograph their capers. The band bounced into the ring, frolicked, dropped down to pray that Clay would stop hitting them. They lined up so he could knock them all out with one punch, then they fell like dominoes. They formed a pyramid to reach Clay's jaw so one of them could pretend to sock it.

Once the Beatles left, Clay worked out, then walked back to the dressing room for a rubdown. As he stretched out on a table, he beckoned me. We'd never spoken. "Who were those little sissies?," he whispered.

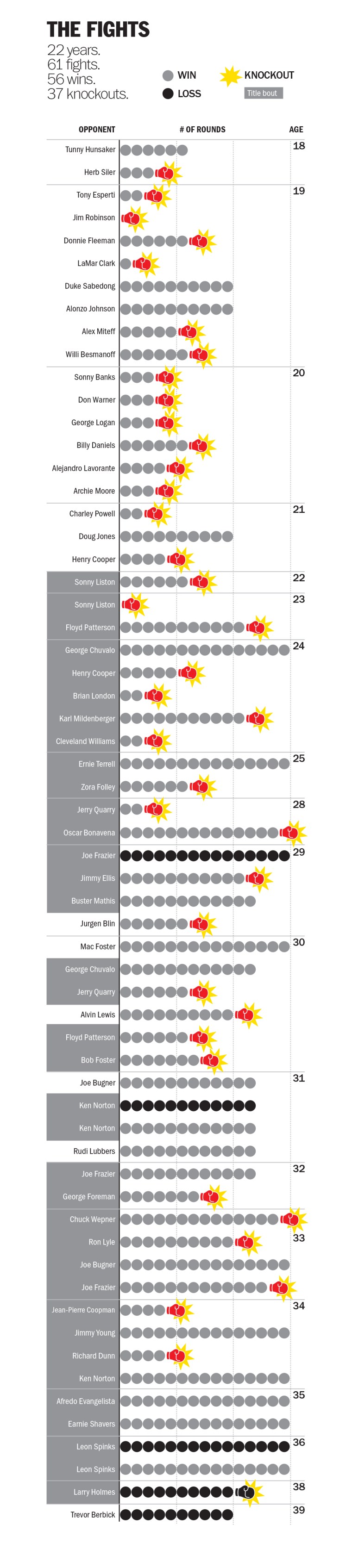

Seven days later, Clay beat Liston to claim the title. He was 22 years old, one of the youngest heavyweight champions of all time, as well as one of the best, the most charismatic and the most controversial. With that triumph over Liston, Clay's trajectory was set: a hero and a villain, then a principled warrior and, finally, a beatified legend, at once misinterpreted and beloved.

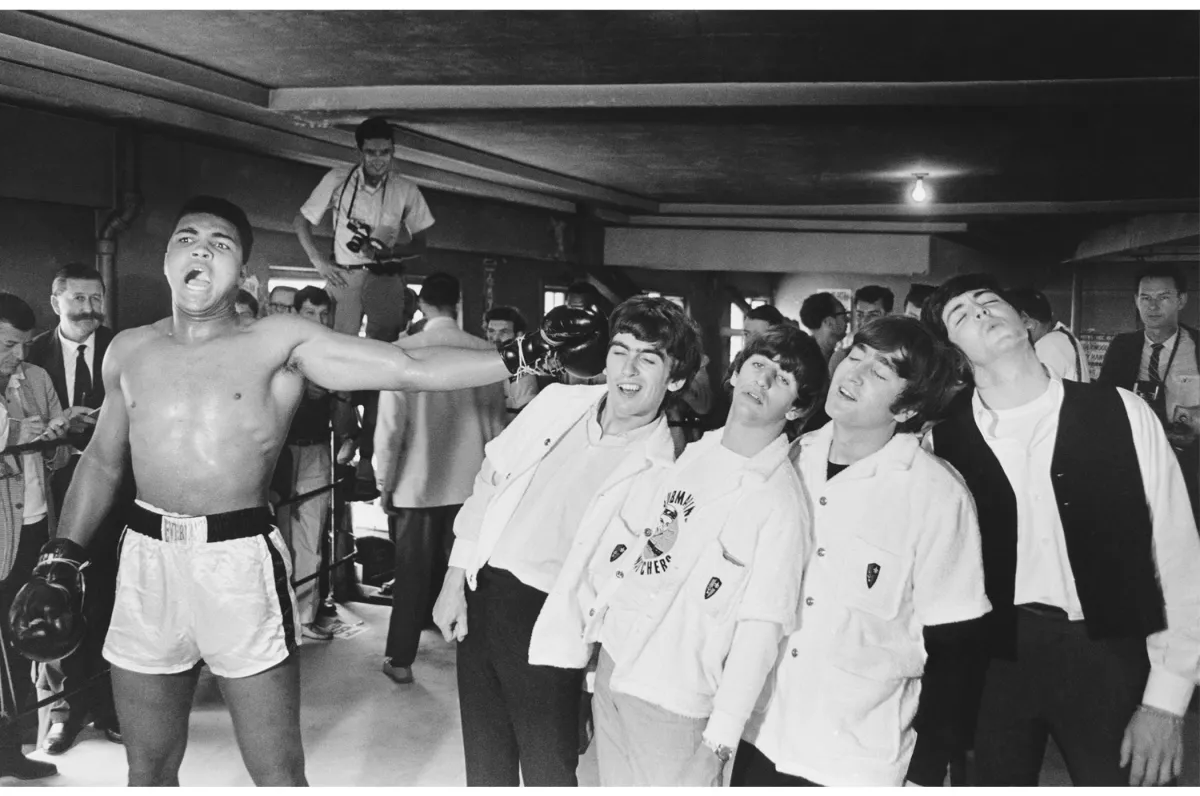

Twelve-year-old Cassius Clay had left his new Schwinn on a Louisville street corner while he gorged on free popcorn at the annual Home Show. When he returned, the bike was gone.

Someone told him to find a police officer. There's one in that basement there. Clay ran down into the Columbia Gym. Boys, black and white, were slamming bags, jumping rope, sparring in front of mirrors as bells clanged and men yelled, "Time!" He was spellbound. Joe Martin, an off-duty white cop who coached young boxers, listened patiently as the boy ranted: "Somebody stole my bike … when I find him I'm gonna whup him, I'm gonna …"

"Do you know how to box?" asked Martin.

Martin would recall that Clay was skinny and "ordinary" as a fighter at first. But he quickly found, as Clay's pro trainer Angelo Dundee would a few years later, that the youngster was impossible to discourage, "easily the hardest worker of any kid I ever taught."

The crude but crowd-pleasing slugger soon became a neighborhood celebrity. Gang members respected him, teachers overlooked his unsatisfactory schoolwork, and, perhaps most important for his confidence, he gained recognition within his father's large and accomplished extended family of teachers, musicians, craftspeople, and business owners. The family traced itself back to the statesman and abolitionist Cassius Marcellus Clay, who freed his slaves. One of them named a son Herman Clay, who in 1912 named a son Cassius Marcellus Clay, who in turn named his firstborn, on January 17, 1942, Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr.

Years later, when I asked Muhammad Ali about his lineage, he bridled. He was a new member of the Nation of Islam then, dogmatic in his anti-white rhetoric, but mindful of his family's pride in its heritage. Finally he said that if there was any white blood, "it came by rape and defilement."

Ali's father instilled in him the sense that he would have to make his way by following white-man rules, at least until he was big enough to make his own. He started making them quickly. Despite resistance from trainers and coaches, Ali evolved a style that probably ruined many other fighters who didn't have his speed and talent. Few could get away with holding their fists at their waist as he did, or with avoiding punches by pulling back instead of "slipping" them, leaning to one side or the other so they passed harmlessly over a shoulder. His style often led people to believe he couldn't take a punch.

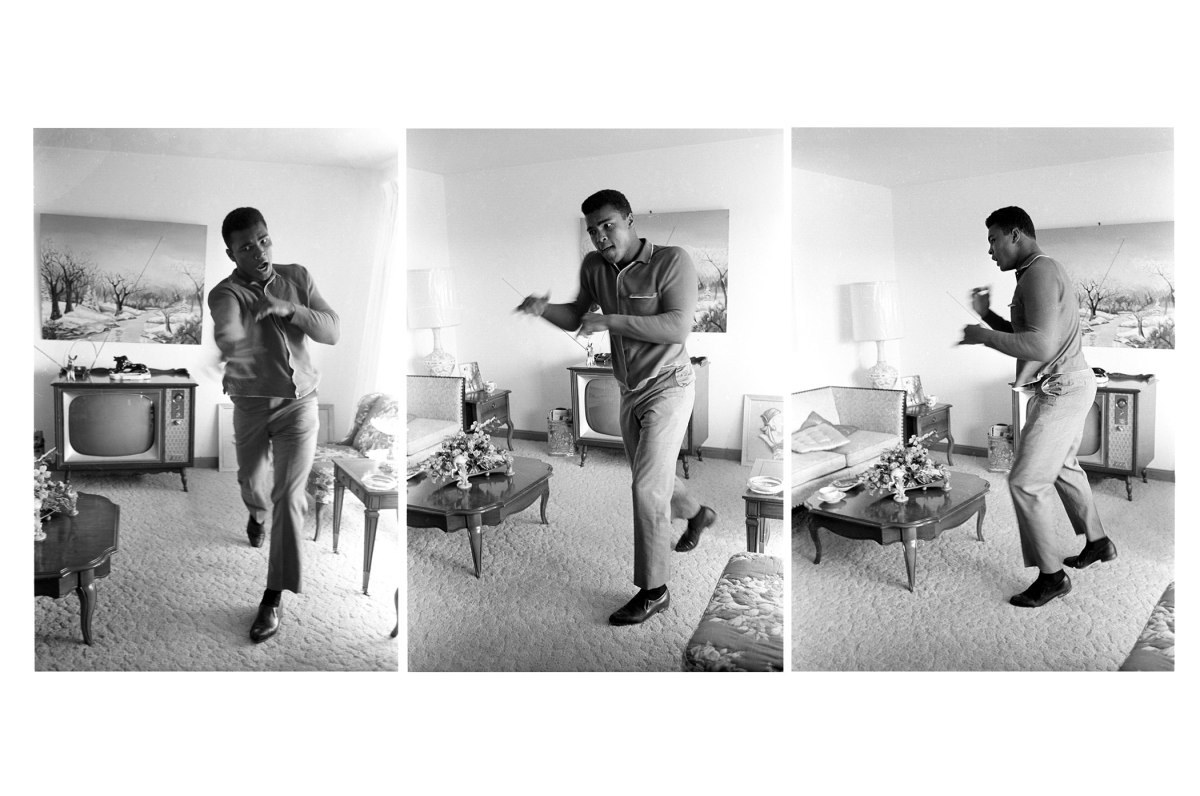

As a teen in Louisville, Clay's boundless enthusiasm, self-promotion, and confidence led him to Angelo Dundee's hotel room. He had heard that the famous trainer was in town. Dundee remembers getting a phone call that went something like: "This is Cassius Clay, the Golden Gloves champion of Louisville, Kentucky. I'm going to be the heavyweight champion of the world. I'm in the lobby. Can I come up?"

The 15-year-old was invited up. And Dundee was soon his trainer. He tended to have that effect on people. Fellow students at Central High remember a big puppy who sweetly and tentatively hit on girls who dismissed him as not very bright and least likely to succeed. But they did enjoy watching him do his daily roadwork, trailing the school bus and shouting that prediction of becoming champion of the world.

He was a sensation at the 1960 Olympics in Rome, a handsome, outgoing 18-year-old light heavyweight with a dazzling smile and a motor mouth. He chased the willowy beauty Wilma Rudolph, winner of three gold medals in track, until she couldn't stop laughing. He took pictures with his box camera. When a Soviet journalist digging for controversy asked about racial segregation in America, Clay said, "Tell your readers we got qualified people working on that, and I'm not worried about the outcome.

"To me, the U.S.A. is still the best country in the world, including yours. It may be hard to get something to eat sometimes, but anyhow I ain't fighting alligators and living in a mud hut."

He would later regret that quote and attribute it to ignorance, but as it flashed around the world he became a symbol of what was right about America and sports, especially back home where anti-communism and racial unrest were coming to a boil. Here was a descendant of slaves grateful for the advantages of democracy, said the pundits; he wasn't agitating to vote or sitting in at lunch counters. He was just knocking down commie boxers with those hammering fists. Did you notice how straight he stood on the medal stand after winning his gold as they played our anthem?

But back home, he was, in his own words and others', the "Olympic nigger." When he was refused service at a restaurant in segregated Louisville, he said later, he threw his gold medal in the Ohio River. This was not true. The medal was stolen when he left it unattended. Like the bike.

After Rome, Dundee steered Ali prudently through 19 mostly underwhelming professional opponents. The fighter's rhyming predictions ("This is no jive. Moore will go in five") delighted us younger reporters. Older traditionalists, who insisted on the gravitas of pugilism, were not amused.

Tickets were moving slowly before the championship bout with Liston. Clay shouldn't even have been there. His greatest accomplishment to that point was appearing on the cover of TIME, more for his looks, personality, and doggerel than for his ring record. The odds were 7–1 against him, a prediction that no poetry could counter, even lines as compelling as:

Yes, the crowd did not dream

When they laid down their money

That they would see

A total eclipse of the Sonny.

(Just how much of his doggerel did Clay actually write? Certainly less than he claimed. Dundee has been accused of lending a pen, as have Drew "Bundini" Brown, his assistant trainer in charge of morale, and even various sportswriters. But the best lines, including the ones above—part of a much longer verse—were written by a well-known comedy writer, Gary Belkin, for an album that Clay recorded, I Am the Greatest.)

The promoters blamed the weak sales on the reports of Clay's membership in the Nation of Islam and his friendship with its most famous spokesman, Malcolm X. Malcolm was in Miami in the week leading up to the fight. According to Manning Marable's exhaustive Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention, he agreed to stay out of sight until fight night in exchange for a front-row seat.

At the time, Malcolm was on the outs with the Black Muslim leader Elijah Muhammad. Clay did not seem to be aware that he'd soon have to choose, with deadly results, between the two men.

With boundless exuberance, Clay tried to hype the gate, talking his trash (before it was thus named)—"Liston even smells like a bear. I'm gonna give him to the local zoo after I whup him"—and repeating his (as it turned out, accurate) prediction: "He will go in eight to prove that I'm great, and if he wants to go to heaven I'll get him in seven."

Clay's critics would later point to that confidence as proof the fight had been fixed. Commentators, though, characterized his posturing as that of a scared boy whistling to keep up his spirits. The mature Ali admitted he had been scared of Liston; in fact, Malcolm had to calm him by saying Allah would not allow him to be beaten.

While Liston's glare reduced the press pack to bland and timid questions, Clay's affability emboldened us. "Exactly what are you going to do," asked a Boston sportswriter a few days before the fight, "when Sonny Liston beats you after all your big talk?" Clay, sprawled on his dressing-room table, blowing kisses at his reflection in a mirror, replied, "The next day I'll be on the sidewalk hollering, 'No man ever beat me twice.' I'll be screaming for a rematch."

Right up until he stepped into the ring on the night of February 25, 1964, there were whispers that Clay, terrified, had fled the country. But the first intimation that he might not have to be rushed to intensive care came the moment he stepped into the ring. The gasp in the arena when the two fighters met for the referee's routine instructions was not in response to Clay's being there but to his superior size. Wasn't this supposed to be David and Goliath?

If it was, the kid had no end of smooth stones to fling. From the start, he peppered the champion's head with lightning jabs and straight rights. By the third round, he had opened a nasty gash under Liston's left eye that would require stitches. He was in control throughout, in trouble just once. In the fifth, he was temporarily blinded by a substance that might have been purposely smeared on Liston's gloves earlier. Clay, thinking he was being poisoned, screamed, "Cut the gloves off." Dundee, experienced and cool, washed out his eyes and pushed him back in the ring. "Daddy, this is the big one. This is for the title. Get in there."

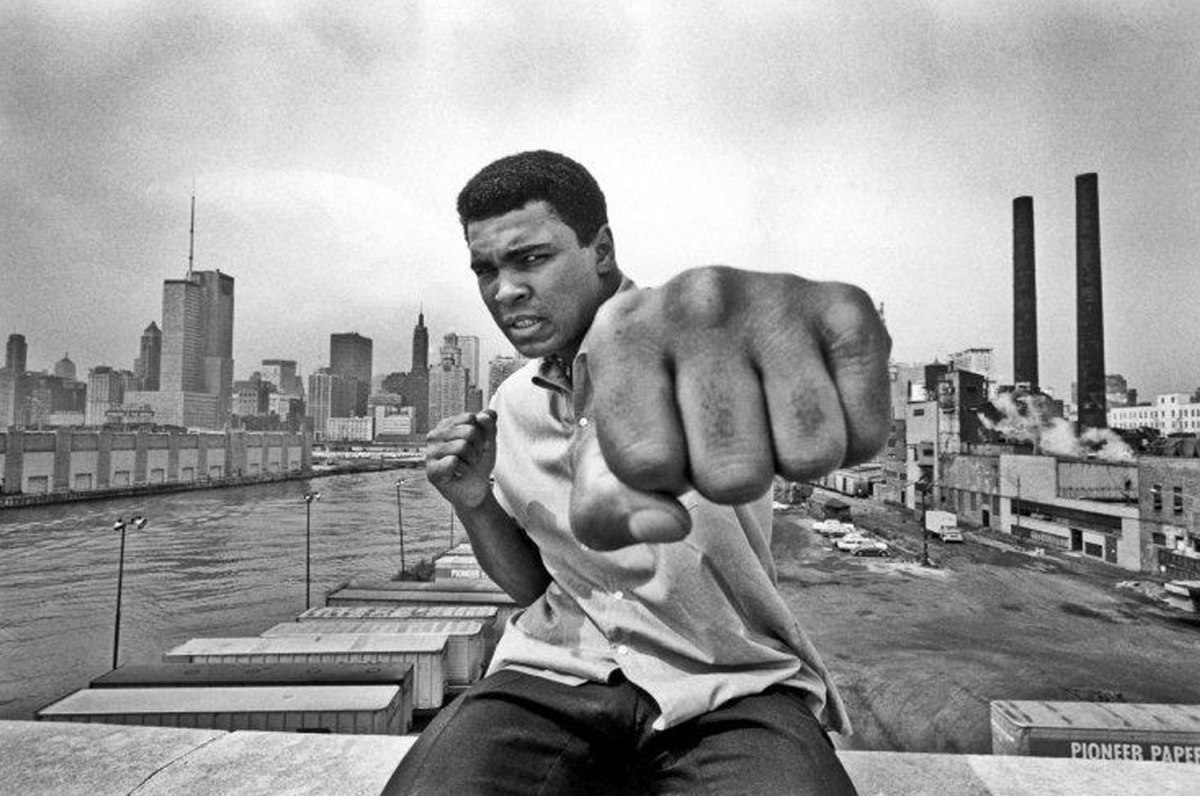

Clay danced until his eyes cleared, then battered Liston with a fresh barrage. Liston slumped on his stool and didn't come out for the seventh round. The champ had quit. Clay leaned over the ring ropes to shout at the press, "Eat your words. I am the greatest! I … am … the … greatest!"

There were rowdy celebrations in Miami Beach that night, but the new champion enjoyed quieter revels. He shared vanilla ice cream with Malcolm and a few Muslim friends. The next morning, Clay confirmed his membership in the Nation of Islam.

Soon he would renounce his "slave name" and demand to be called, in the Black Muslim manner, Cassius X. And then, in what Marable describes as an attempt to subvert Malcolm's influence on the young convert, Elijah Muhammad bestowed a new name, Muhammad Ali, which he said meant "worthy of all praise most high."

The press mostly refused to honor the name change, trying to finesse it by calling him, simply, "Champ." He was routinely described as "ungrateful" to a system that had made him famous and rich (although corporate endorsements stayed out of reach). At the least, he was "brainwashed" and "misguided." Jimmy Cannon, the influential columnist who had once written that "Joe Louis is a credit to his race, the human race," called Ali's ties to the Nation of Islam "the dirtiest in American sports since the Nazis were shilling for Max Schmeling as representative of their vile theories of blood."

The undisputed heavyweight champion of the world—at a time when that title had significance—was turning his back on mainstream religion, politics, and commerce. He was making a powerful statement in the turbulent '60s as race riots swept the cities, voter-registration workers were attacked and murdered in the rural South, and the Vietnam War was expanding. That statement was interpreted—by both supporters and critics—to mean that Ali was an outspoken agent of change. Often in ways he did not fully understand and might not have approved of if he had, Ali was increasingly seen as the mouth and muscle of the American counterculture.

Ali went into training for his rematch with Liston amid rumors of the first fight being fixed, including a scenario in which the Muslims had threatened to kill Liston if he hurt their man. Another rumor had the Mafia ordering Liston to tank the fight since he had a return-bout clause, which promised a larger payday.

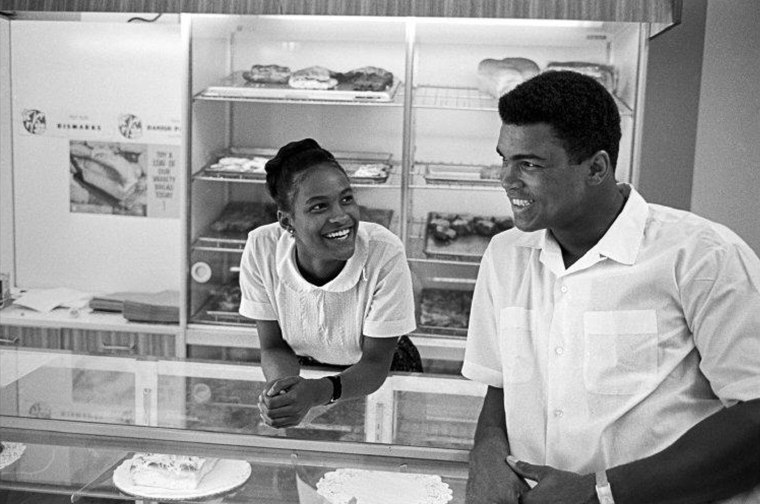

The 15 months between the two title fights with Liston were tumultuous for the new champ. He married a pretty Chicago cocktail waitress, Sonji Roi, a single mother a year older than he.

The marriage was brief; Roi was not a Muslim and she had plans of her own, which included weaning her husband from the sect.

The divorce was one example of Elijah Muhammad's hold on Ali. Another was Ali's choice of the sect leader over his "big brother" Malcolm.

When Ali and Malcolm crossed paths in Ghana in the spring of 1964, the "little brother" not only snubbed Malcolm, he mocked his new beard and "funny white robe" to a New York Times correspondent. He added: "Man, he's gone. Nobody listens to that Malcolm anymore." According to Marable, these were words "he would later regret."

I'm sure Marable was right. Talking to Ali about the incident on several occasions years later, I found him at a rare loss for words. He just didn't want to talk about it. He mumbled something about being wrong, being young, being afraid. He would tell his biographer Thomas Hauser that "what Malcolm saw was right, and after he left us, we went his way anyway."

Malcolm was deeply hurt by Ali turning away from him. I think he must also have known that their friendship offered a certain level of physical protection. As long as he was under the champ's aegis, he would not be punished for his Black Muslim apostasy.

On February 21, 1965, Malcolm was gunned down in a Harlem ballroom where he was about to make a speech for his new organization. That night there was a fire in Ali's apartment, and he briefly went into hiding, saying that he thought he had been targeted, too.

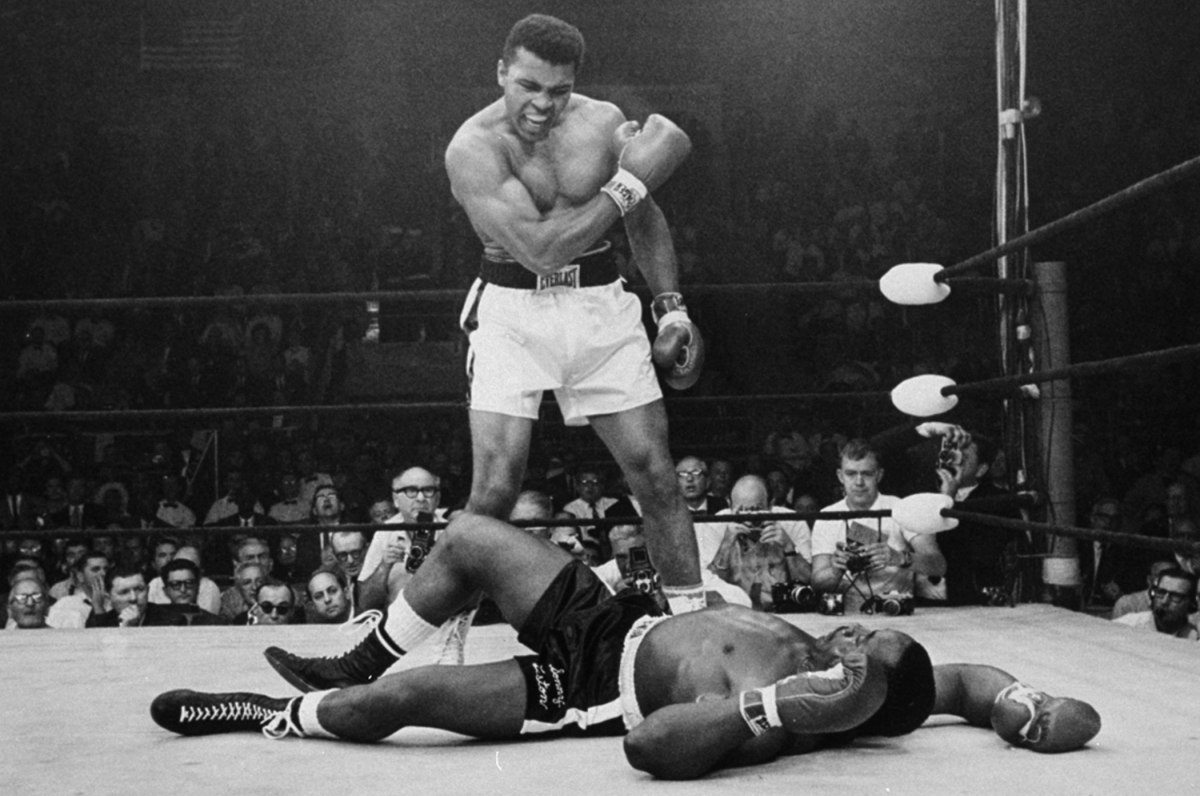

Three months later, Malcolm's murder was the shadow over Ali's first title defense, the rematch with Liston. Rumors of a carload of gunmen from New York heading toward Lewiston, Maine, to avenge Malcolm by shooting Ali made police officers, reporters, and fans jittery. But the closed-circuit-television promoters were probably thrilled that their ticket sales would soar if fans anticipated a title fight and an assassination attempt. And they added to the spectacle by announcing a one-night, $1 million life-insurance policy on Ali.

On fight night, the security was ludicrous. Troops of cops searched women's handbags while local kids climbed into the shabby ice-hockey arena through the windows. Liston seemed the least concerned of all. "They coming to kill him, right?" he said.

The fight officially lasted one minute, 52 seconds, some of which was because of confusion in the ring. In that first and only round, Ali tagged Liston on the jaw with a short straight right — his third good punch — that knocked Liston down. At that point the referee, the former heavyweight champion Jersey Joe Walcott, lost control of the bout. Ali was not immediately sent to a neutral corner. The timekeeper seemed to lose the count. Liston was down, all right, but was he really out? Some called it the "phantom punch" because they never saw it. Others claim it was the perfect punch. I was at ringside, sitting beside Howard Cosell, who had a TV monitor. We watched the punch over and over until we thought we saw it.

It wasn't a bad metaphor for the emerging image of Ali, a 23-year-old holy child, simple and complicated, on his way to becoming the most recognizable face on the planet. If you looked at him hard enough and long enough he would come into focus as whatever it was you wanted him to be.

With the unbeatable Liston beaten, Ali set out to establish himself as the indisputable champion by knocking off all contenders. First on the list was former champ Floyd Patterson. Patterson approached the fight as a crusade for Christianity and America. Ali had returned from a trip to Africa saying he was "not no American. I'm a black man." He inveighed against "the spooks and ghosts" of the white man's religion that enslaved black folks by promising them "pie in the sky when you die by and by," thus distracting them from trying to "get it down on the ground while you're still around."

Patterson declared, "The image of a Black Muslim as a world heavyweight champion disgraces the sport and the nation. Cassius Clay must be beaten and the Black Muslim scourge removed from boxing." It was the invoking of his slave name that particularly riled Ali.

The social, political, economic, and cultural winds swirling around the Ali-Patterson fight were briefly stilled by the disgusting exhibition of the fight itself. Patterson was game, but he had no chance. Ali mocked and humiliated and punished Patterson. The crowd called for the ref to stop the slaughter, or for Ali to be merciful and knock out his opponent. But Ali just kept jabbing and jabbering, "No contest, get me a contender … boop, boop, boop … watch it, Floyd." The referee finally stopped the 15-round fight in the 12th.

By now, Ali had settled in to the personae that would shape the perception of him for years. For the government, he was a dangerous example of an anti-establishment sports hero just as it was depending on the loyalty of American youth to support an expanding war. Conservative working-class patriots, the pool that has traditionally supplied so many soldiers, called Ali a coward and an ingrate. College boys and antiwar liberals revered him as a brave rebel. Radicals, like Black Panther leader Eldridge Cleaver, saw him as a rousing example of the "autonomous" black man who is beyond government control. The boxing establishment, meanwhile, was concerned that Ali was stepping outside its control.

The contenders who lined up to fight Ali didn't necessarily look more promising than Patterson. It didn't seem as if the young champ was about to be defeated by a modern "great white hope" (of any color) in the ring. He was going to have to be defeated outside it. And he gave the opening.

Some people wondered if Ali's 1-Y deferment in 1964 ("not qualified under current standards for service in the armed forces") had been a gift from the Louisville draft board to the local pillars who owned his contract, and if the sudden reclassification to 1-A in 1966 was a reaction to that contract's end. Others speculated that Ali had been deemed mentally unstable or homosexual to earn the earlier classification, because he certainly seemed smart enough to serve.

As it turned out, those 1964 tests determined he wasn't smart enough. Ali had struggled to answer the questions, especially the math, and his Army IQ was listed as 78, well below the passing grade. He was retested, and failed again. Two years later, Ali hadn't suddenly become smarter. The Army had just lowered its standards to meet its quota of fresh young bodies.

The champ was humiliated. If he blithely told reporters, "I said I was the greatest, not the smartest," he had always been embarrassed by a weak high-school academic record and poor reading skills. On several occasions, he admitted to me that he had never been able to complete an entire book, including the Koran.

That humiliation was the main reason he first said, "I ain't got nothing against them Vietcong." He may have been the most quotable athlete of all time, and most of his utterances were joyous. But his most famous quote was explosively polarizing.

Three months after he poked Patterson apart, the country was pulling apart. On television that day, Feb. 17, 1966, Senate hearings raged over the war in Vietnam. Sharp political lines were being drawn, but Ali was oblivious. As a swarm of reporters descended on his rented Miami bungalow for his reaction to the reclassification, I watched his mood change over that long afternoon. It began with bewilderment and morphed into questioning.

As fellow Muslims, many of them World War II and Korean War vets, arrived, Ali grew more manic. They told him that cracker sergeants would see he was shipped to the front lines and snickered that they would drop grenades down his pants. News trucks continued to roll up. Interviewers, sensing his anger, provoked him further. "Do you know where Vietnam is?"

"Sure," he mumbled, although he didn't sound sure.

"Where?"

He shrugged. I would have shrugged, too. This went on and on. It was dusk when a newcomer with a mike asked the question for the hundredth time: "What do you think about the Vietcong?"

And that was it. "I ain't got nothing against them Vietcong." The sound bite that would help define the '60s, the headline that made him simultaneously hated and beloved—and that he would repeat in various versions and come to believe—was not on that day meant to be a political declaration. It was just the whiny response of a worn-out and exasperated young man.

The adverse reaction was so quick, it felt as though the politicians, the boxing commissions, and the older sportswriters had been lying in ambush waiting for that quote. The vaunted Red Smith wrote: "Squealing over the possibility that the military may call him up, Cassius makes himself as sorry a spectacle as those unwashed punks who picket and demonstrate against the war."

Despite the storm, Ali was a busy champion, with seven more title defenses in 12 months. He said he didn't want to go to jail for refusing to be drafted if his conscientious objector claim was denied, but the alternative—joining the Army and giving exhibitions for the troops—was worse. "What can you give me, America," he said in a tone as bleak as the sky, "for turning down my religion? You want me to do what the white man says and go fight a war against some people I don't know nothing about, get some freedom for some other people when my own can't get theirs here?" His voice deepened. "Ah-leeee will return. My ghost will haunt all arenas. Twenty-five years old now. Make my comeback at 28. That's not old. Whip 'em all."

It would turn out to be his best prediction.

On April 28, 1967, Ali refused induction. Boxing commissioners, who are mostly political appointees, withdrew their recognition of his championship and refused to license him to fight in their state or municipality. Ten days later he was arrested and released on bail. Thus, he was effectively stripped of his livelihood before he was convicted of any crime. On June 20, after 20 minutes of deliberation, a jury did convict him. The judge imposed the maximum sentence: five years in jail and a $10,000 fine. He would go into exile, but never to prison.

That summer he married a tall, striking 17-year-old Muslim woman, Belinda Boyd, who changed her name to Khalilah Ali, and dropped out of public view. But his influence was growing. Athletes, particularly black athletes, were inspired by his story to stand up for equality in their sports and in the larger society. This was most dramatically epitomized by the Black Power salute at the 1968 Olympics, which derived much of its energy from what was seen as the persecution of Ali. While the movement began with black football players and track athletes, it would eventually influence the baseball players who demanded free agency and the white tennis players who forced an end to the sham of amateurism. Led by Billie Jean King, these tennis players fought for transparency and gender equality in prize money.

Whites who heard Ali on the college lecture circuit—his main source of income during his exile from the ring—were getting a window on social, political, and religious issues, as well as on black attitudes. Blacks were finding a symbolic leader. Ali himself, able for the first time to concentrate on current events and prodded by the questions asked by his audiences, began to more fully understand his views on the war in Vietnam, religious persecution and civil rights.

And he was making some large, sweeping statements. On being banned from the ring, he said: "You read about these things in the dictatorship countries, where a man don't go along with this or that and he is completely not allowed to work or to earn a decent living."

His take on race relations might have been considered simplistic, but it was direct and strong: "The white race attacks black people. They don't ask what's our religion, what's our belief? They just start whupping heads … So we don't want to live with the white man, that's all."

What he wanted, he said, was a black homeland. "We were brought here 400 years ago for a job. Why don't we get out and build our own nation and quit begging for jobs?"

During this period, the sportscaster Cosell was critical in keeping Ali's name alive. He interviewed him on TV and used him as a commentator on fights. Without ever directly endorsing Ali's opinions, he defended Ali's right to have them. As a lawyer, Cosell maintained that Ali's constitutional rights had been violated when his title was stripped without due process. His support helped Ali through a difficult time.

I was present at one poignant reminder of how long a fall from a throne can be. Ali was the mystery guest on What's My Line?, a popular TV show in which blindfolded panelists tried to deduce a guest's identity with yes-or-no questions. It was his second appearance on the show. In 1965, his identity had been discerned in minutes. In 1969, he remained a mystery all the way to the buzzer.

It was the starriest fight night in Madison Square Garden history. Frank Sinatra was at ringside, shooting pictures for LIFE magazine, and Burt Lancaster was behind a microphone, broadcasting to the closed-circuit-TV audience. Ethel Kennedy, Hugh Hefner, Marcello Mastroianni, Abbie Hoffman … they were only the supporting cast.

The stars were two undefeated heavyweights, each with a legitimate claim to the championship. Nothing like this had ever happened before.

Each fighter was guaranteed $2.5 million, a record, but ultimately a bargain for the promoters. The Garden was sold out (the top ticket price, $150, was unprecedented, and the the re-sale market was getting $1,000). It has been estimated, perhaps somewhat extravagantly, that 300 million people worldwide saw the fight and that it grossed more than $18 million.

Beyond the glitter and the gold was an intense drama. Some saw The Fight as Ali's triumphant return from exile to reclaim his rightful throne. Others felt that Frazier, honest workman and blue-collar patriot, would close the book on the treasonous con man.

"After a while, how you stood on Ali became a political and generational litmus test," Bryant Gumbel told Hauser. "He was somebody we could hold on to; somebody who was ours. And fairly or unfairly, because he was opposing Ali, Joe Frazier became the symbol of our oppressors."

Frazier was also the standard-bearer for the boxing establishment. In a press release for The Fight, the Garden declared of him, "Not since the days of Joe Louis and Ray Robinson and Floyd Patterson has a black man brought so much dignity to boxing."

The Fight was possible because the mood of the country had changed during Ali's exile from the ring. By 1970, more and more Americans felt free to say that they, too, had nothing against them Vietcong. Ali's appeal of his conviction for draft evasion had reached the Supreme Court. Based on other decisions, there were indications that he would win. Meanwhile, the radicals' cry of "Black Power!" had been translated by truly powerful blacks—civil-rights leaders, politicians, entertainers, business owners—into clout.

Ali, inactive for three and a half years, had beaten a solid white heavyweight Jerry Quarry and needed one more warm-up. A match in New York, at the Garden, would be the perfect run-up to The Fight. But at first the New York State Athletic Commission refused to license him. Not until the NAACP Legal Defense Fund prepared an eye-opening list of convicted felons who had been licensed to fight by the commission did a federal court order that politically appointed body to issue Ali a license.

On December 7, 1970, six weeks after stopping Quarry, Ali scored a 15th-round technical knockout over Oscar Bonavena at the Garden. Because he knocked Bonavena down three times in the last round, people tended to forget how much trouble he'd had with the tough Argentine power puncher through the previous 14. Was he really ready for The Fight—and the second act of his career—scheduled for March 8, 1971?

Verbally, he was. Ali started with a poem that ended, "This might shock and amaze ya but I'm gonna destroy Joe Frazier." Then he really cranked up the vicious jabs. He said, "Anybody black who thinks Joe Frazier can whup me is an Uncle Tom." And then, "Joe Frazier is too ugly to be champ. Joe Frazier is too dumb to be champ."

There is no way to justify Ali calling Frazier a tool of the white man, much less mocking his dark skin and thick lips by describing him as a "gorilla." Defending the taunts as the routine ridicule of the ghetto, made no sense coming from a self-righteous religionist of Ali's grandiosity. The derision is even more despicable if it was merely a means to boost ticket sales, putting commerce before decency. No wonder Frazier carried a grudge for years.

"I never liked Ali," said Frazier long afterward. He admitted that it hurt to be demeaned by a man he had tried to help during the exile years, even lending him money.

Ali understood that winning would not be enough. He would have to forge beyond mere victory into the bloody hellstorm of Frazier's fury. He would have to prove, at any cost, that he was as much man as Smokin' Joe, that he could stand toe to toe and slug it out with the slugger. Ali was making a devil's bargain: a finesse fighter who had relied on speed and deception—and who was clearly rusty—was going to mix it up with a fearsome banger willing to take three punches to deliver one.

It was not until years later, when Ferdie Pacheco, his longtime doctor, talked to Hauser, that we came to realize just how much Ali had lost in his exile. His legs and hands had suffered the most. Before each bout, Pacheco injected his fighter's fists with drugs, including cortisone, to numb the pain. Where once Ali's quick, dancing movements had been his first line of defense, now he could be hit.

That was a mixed blessing. Ali learned he could take a punch. He became braver—and lazier—allowing opponents and even sparring partners to hit him. He said he was toughening up his body and head. But he was also absorbing lifetime damage, which was about to be accelerated during 15 of the most grueling, pitiless rounds that the sweet science had ever seen.

The crowd had expected Frazier to come out smokin', trying to bull Ali around the ring, offering up his own rugged face in sacrifice to an eventual victory. He did not disappoint. Ali's strategy was a shock, though. Everyone had expected him to dance, to jab and spin, stick and run, to make Frazier chase him. But he did not run. After the first two rounds, Ali planted his feet and fought. His idea was to stand against the ropes and let Frazier bang against his arms and shoulders until he was all punched out. Ali underestimated Frazier's strength, conditioning, and sheer will.

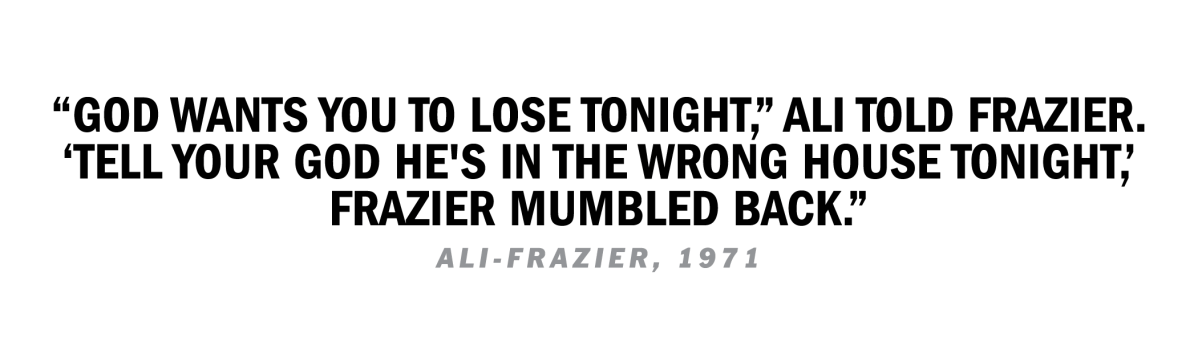

In the third, Frazier landed a solid left to Ali's face. Ali shook it off, then told Frazier, "God wants you to lose tonight." Frazier mumbled back, "Tell your God he's in the wrong house tonight."

Through the middle rounds, Frazier drove the momentum of the fight, moving inexorably forward to hammer Ali with his left hook. Ali scored with jabs to Frazier's face. "It was horrible watching their features change," said said the referee, Arthur Mercante.

Frazier dominated most of the later rounds. In the 15th, he landed a left hook on Ali's jaw. Ali went down. He jumped right up, but by then it didn't matter. The three official scorecards were unanimous in the decision—11 rounds for Frazier and 4 for Ali; 9–6; and 8–6, 1 even.

The physical toll was evident. Frazier's face was misshapen and skinned. Ali, for the first time in his career, looked as if he'd been in a fight. His face was lumpy and blotched, his body marked and sore.

Pacheco remembered that back in the dressing room he had to help clothe Ali, who was "like a drunk; he just lay there limp." At a hospital, X-rays of Ali's swollen jaw were negative, but Pacheco wanted him to stay overnight for observation. Ali refused because "he didn't want anybody saying Joe Frazier put him in the hospital." Frazier, meanwhile, was admitted for internal injuries.

Both men won that night. Frazier had emerged from Ali's shadow. He was the undisputed champion. Ali's "heart," his courage in the ring, had never been tested; now it was no longer suspect. There was no question that he could take it. That, combined with people's grudging admiration for his sincerity, his willingness to sacrifice money and career for principle, started him on a path to widespread public redemption. (Three months later, there was legal redemption. The Supreme Court reversed his 1967 draft-evasion conviction.)

The morning after The Fight, a serene expression on his beaten face, Ali entertained waves of media in his hotel room. They all seemed more concerned about the loss than he did. I stayed for hours in that room, marveling at his mood. Didn't he know he was over, that from here on he would be considered an "opponent," a has-been? How could he be so … philosophical? I thought about the first time I'd met him, before the Liston fight in Miami, when he told a reporter that if Liston won, Ali would be out on the sidewalk the next day hollering, "No man ever beat me twice."

During a lull between waves of reporters, I reminded him of what he had said that day. He nodded, closed his eyes, and began to chant, "Fight him again … I'll get by Joe this time … I'll straighten this out … I'm ready this time … You hear me, Joe? … YOU HEAR ME? … Joe, if you beat me this time, you'll really be the greatest."

Frazier, though, remained undisputed heavyweight champion for less than two years. Another unbeatable monster had arisen. In 1973, George Foreman knocked him down six times in the first two rounds before their fight was stopped. Foreman—huge, implacable—was now the champ. It was generally assumed that the fighter who would beat Big George was still a child.

Ali, who was 31, had hoped for a rematch with Frazier to reclaim his title. Now his future looked like an endless procession of good-but-not-great fighters he could dominate for excellent paydays and very good fighters who would climb over him on their way to Foreman. The conventional wisdom was that Ali's dream of a return to the throne was dead.

Nevertheless, he was busy, with 14 fights in three years. He beat Patterson and Quarry again, as well as his old boyhood pal and sparring partner Jimmy Ellis. He took on all comers, losing only once, to Ken Norton, who broke his jaw. Six months later he avenged the loss. And he did fight Frazier again, at the Garden, this time winning a unanimous 12-round decision. People close to Ali noticed that he was taking more punishment.

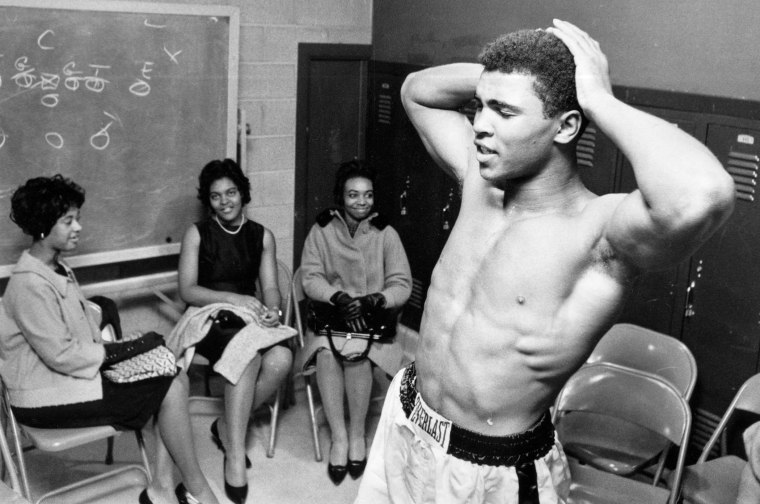

Although he was no longer the champ and his life with Khalilah and their four children was a frequent subject of feature-story idealization and his own rhapsodizing, Ali was relentlessly promiscuous. Pacheco described him as "bountiful in his pelvic generosity." He would often have sex with a half-dozen women in the same day, according to members of his inner circle. Ali didn't want to disappoint any of them; in his accounting, his pelvic generosity wasn't much different from his munificence toward autograph seekers. Members of the Ali Circus noted that the women he pulled into the tent were of all sizes, ages, and degrees of beauty, although, they all maintained, he never had sex with white women. Ali told Hauser that his promiscuity was wrong but understandable. He was just so pretty!

Eventually, there was no one left to fight except Foreman, against whom, boxing experts agreed, he stood no chance. Foreman was Liston-like, boorish and brutish, in those days before he found God and became a cuddly and lovable grillmeister. But there was one more dangerous character on the boxing scene: Don King, an ex-con from Cleveland. King, who had killed two men in the line of his duty as a leading numbers banker, was a familiar figure at fights before he began promoting them. Tough, wily, intimidating—and with an electrified Afro and gift of gab (his catchphrase: "Only in America!")—King worked his way into Ali's circle. He was adept at playing the race card. Why would a black boxer fight for white promoters when he could give business to one of his own kind?

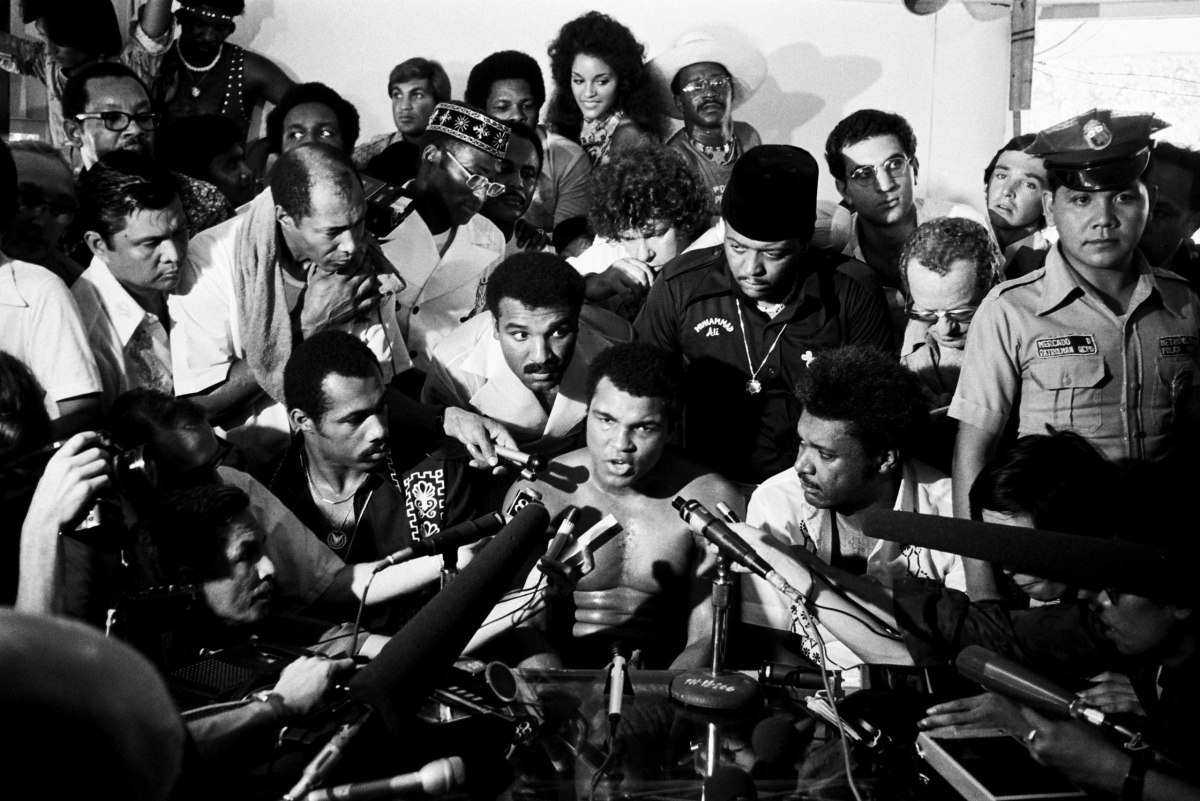

Litigious and shameless, King settled cases with Ali, Mike Tyson, and numerous other fighters after they sued him for cheating them out of money and contractual rights. But that was only after he made his bones as a promoter in 1974 by pulling off one of boxing's most storied events, the Rumble in the Jungle. Who better to deal with Mobutu Sese Seko, the dictator of Zaire? King negotiated a record $10 million purse for Foreman and Ali, guaranteed by the Zairean government.

And so it came about, like the telling of a tall tale, in the dark stillness of the hour before dawn, beneath a waning African moon. Foreman, the favorite, shrugged his cannonball shoulders and stared balefully at his challenger. Now 25, he had never been knocked off his feet in a prizefight, and he was heavier than Ali, who at 32 was considered in the twilight of his career.

But as they met in the middle of the ring, Ali smiled and softly said, "You have heard of me since you were young. You've been following me since you were a little boy. Now you must meet me, your master."

Millions around the world tuned in on closed-circuit television. (In the stadium in Kinshasa thousands began to chant, "Ali, bomaye"—Ali, kill him.

As Ali waited for the opening round, Bundini's voice cut through the swelling roar of the crowd. "Remember what I said: God set it up this way. This is the closing of the book. The king gained his throne by killing a monster, and the king will regain his throne by killing a bigger monster. This is the closing of the book."

At the bell, the two big men charged to the center of the ring. They paused, then warily began to circle each other. Ali delivered the first punch, a solid right to Foreman's head. Foreman lunged forward. Ali grabbed him around the neck and pushed his head down. Foreman was enraged. No one had ever hit him so hard, so early, then dared to test his strength by grappling with him.

A few minutes later, Foreman drove Ali into a corner and began to pound him. The crowd groaned. Ali was trapped. Experts at ringside buzzed. Ali wasn't dancing, he was merely bobbing from side to side. Foreman had prepared to battle a moving target. A mechanical fighter who couldn't adjust easily to unexpected tactics, he just kept poking away at his stationary opponent, landing blows where they could do no real damage. The ropes Ali leaned on helped cushion the force of the punches. Except for a hard shot to his head in the second round, he didn't seem to be getting hurt. And when he struck back, quick jabs and rights connected with Foreman's head. Ali taunted the champion: "You are just an amateur, George. Show me something. Hit me hard."

By the fifth round, Foreman's face was swollen from the jabs and he stood on heavy, slow mummy legs. Frustrated, he decided to go all out for a knockout. He unleashed a barrage of thundering blows, his best shots, crunching rights and wicked left hooks. And still Ali stayed upright, leaning against the ropes. Foreman was breathing hard, his punches finally losing power, his mind losing confidence. He paused.

And Ali pounced. His hands a blur, he fired punch after punch, thunderbolts. One right cross almost turned Foreman's head around.

In the eighth, Ali unleashed what some consider his finest punch ever. Saved up since he was 12 for the thief who stole his bicycle, he now used it for the pretender on his throne. First, three good rights and a left. Then the bomb, a right-hand sledgehammer.

Foreman leaned forward from his waist as if he were folding up. Then he pitched onto the canvas. Ali had killed the monster, closed the book, and regained his championship.

Then he fainted.

Back on his feet in seconds, he yelled at the press, "What did I tell you?"

Ten years after Clay beat Liston, America responded to the champion Ali. There were parades in Chicago and New York, and a visit to the White House.

"The championship," Ali said one night in a mellow mood, "is top of the world."

And did he ever enjoy being back on top. He would wander out of his hotel or stop his car to suddenly appear on a city street or in a shopping mall, watching out of the corners of his eyes as passersby stopped, turned, did a double take, and whispered, "Is that…?" and then, convinced by his welcoming smile that indeed it was, stampede toward him shouting, "Ah-leeee." Ali opened his arms to them all.

I was with him once on a high-school football field near Daytona Beach. Ali had just finished a joke-a-poke exhibition match for charity, and now he was back in the motor home he used as a dressing room. He shooed everyone out, then leaned from the doorway to survey the crowd until he had picked out three foxy young women, whom he invited in. A few minutes later, two emerged from the trailer's entrance. Ali grinned at us as he closed the door again.

I watched as the motor home began to jiggle on its springs. The champ was floating and stinging. "Don't write about this," said Dundee. One of the press agents added, "Not if you ever want to interview him again."

I gave the ultimatum a few minutes' thought on the flight home. After more than a decade, my access would be over. That would be too bad. I felt a little sad. Goodbye, Ali, thanks for the ride.

The Times Magazine titled the piece "King of All Kings." It ended with the jiggling motor home.

I should have known better. The next time we saw each other, a few months later, Ali rushed over and said, "King of all kings. Right!" Then he invited me to come listen to him some more.

He defended his title three times before meeting Frazier in the third of their classic matches, the Thrilla in Manila, another King promotional masterpiece, this one for the dictators of the Philippines, Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos. Many people regard the 1975 fight as not only the best of the three but one of the best of all time.

A head-turning presence in Manila before the event was Veronica Porche (later often spelled Porsche, with her blessing), a willowy beauty Ali had met during the American promotional tour for the Rumble. In Manila, Ali took her to a reception at the Presidential Palace, and when President Marcos said, "Your wife is quite beautiful," Ali responded, "Your wife is beautiful, too." The ace Newsweek correspondent Peter Bonventre, who had been struggling with whether or not to mention Veronica, now felt he had no choice.

Twenty-four hours after the piece and its newspaper follow-ups appeared, Khalilah was on her way to Manila. She stayed just long enough to scream at her husband, throw hotel-room furniture, and threaten to break Veronica's back if she ever saw her again, before storming out and returning home.

The actual fight was even more grueling, 14 rounds in late-morning temperatures that approached 100 degrees. Ali started strongly, then lay on the ropes through the middle stages as Frazier piled up points. In the waning rounds, Ali sprang back and took over. The bout was stopped before the 15th, after Frazier's trainer looked at the swollen-shut eyes of his fighter and refused to allow him to continue. Ali was on the brink of quitting too. Later, he'd say that the fight was the closest thing to death he'd ever experienced. "They were fighting," said the Newark Star-Ledger��s Jerry Izenberg, "for the heavyweight championship of each other."

As expected, Khalilah and Ali divorced, and he married Veronica, with whom he had two daughters—including one, Laila, who would grow up to be a boxer like her father. In the next few years Ali published a mediocre, intermittently truthful autobiography, The Greatest, and starred in its movie version; appeared as an ally of Superman in a DC comic; and endorsed a roach killer. There were also some forgettable fights.

By then, Pacheco was worried not only about Ali's physical condition but about his psychological state as well. "Ali is now at the dangerous mental point where his heart and mind are no longer in it," he said. "It's just a payday. It's almost as if an actor had played his role too long. He's just mouthing the words."

But actors don't routinely get smacked in the head. After a brutal fight with Earnie Shavers, a journeyman he once would have handled deftly, Ali said in a slurred voice, "Got hit so hard my ancestors in Africa turned over in their graves." And then, in a stunning upset, he lost his title to Leon Spinks, an Olympic light-heavyweight champion with only seven professional bouts. Spinks was shorter and lighter than Ali. No one, including Ali, had given Spinks much of a chance; the champ showed up pudgy and unprepared to box 15 rounds with a man 12 years younger. Spinks won by a split decision, but he won.

Seven months later, Ali took the title back from Spinks, making him the first to capture the heavyweight championship three times. It was time to close the book. To the great relief of those who cared about him, he retired.

Ali in retirement was depressed by his deteriorating physical condition and the loss of adoring attention. He did not become the world's greatest movie actor—although he did star in a TV miniseries, Freedom Road, with Kris Kristofferson, in which he played an ex-slave who became a U.S. senator after the Civil War. The New York Times review began, "A glaring distinction of 'Freedom Road' is that it takes Muhammad Ali, certainly one of the more vibrant personalities of this century, and makes him dull."

Nor did he become the world's greatest businessman. Ali participated in a number of shaky financial ventures, and nothing much came of any of them. Worse were the shady deals in which his name was used. In one, an Ali associate made phone calls mimicking his voice in an attempt to initiate legislation that would enrich them both.

Ali's hopes of becoming a roving champion for peace and good will were derailed by an actual official assignment. President Jimmy Carter sent him to Africa to gather support for a boycott of the 1980 Moscow Olympics, a response to the Soviet Union's invasion of Afghanistan. Ali was surprised and hurt by his reception in Nigeria, Tanzania, Kenya, and Senegal, where local politicians and journalists asked why he was letting himself be used as a Cold War propaganda tool. When he did a diplomatic shuffle, allowing that he might be wrong and needed to rethink his mission, the State Department quickly shut him down and sent him home.

Ali moved with Veronica into a seven-bedroom mansion in the Hancock Park section of Los Angeles. There wasn't enough money coming in to sustain the lifestyle for very long.

Ali moved with Veronica into a seven-bedroom mansion in the Hancock Park section of Los Angeles. There wasn't enough money coming in to sustain the lifestyle for very long.

Financial pressures made Ali vulnerable to King, who still saw a cash cow fat for slaughter. In 1980, King matched him with the reigning champion, Larry Holmes. Even Holmes, who had once been his sparring partner, had misgivings. He loved Ali. Ali looked fine. But his gray hairs were dyed black, and a slimmer silhouette was the result of a debilitating diet; after ballooning to 250 pounds he had too rapidly dropped to 217. In the ring, he was sluggish. Holmes won every round until Herbert Muhammad and Dundee stopped the fight after the 10th. Sylvester Stallone—who had modeled his character Rocky on an Ali opponent, Chuck Wepner—said it was "like watching an autopsy on a man who's still alive."

Ali fought once more, in December 1981, in the Bahamas, against Trevor Berbick. He lost the decision in 10 dreary rounds.

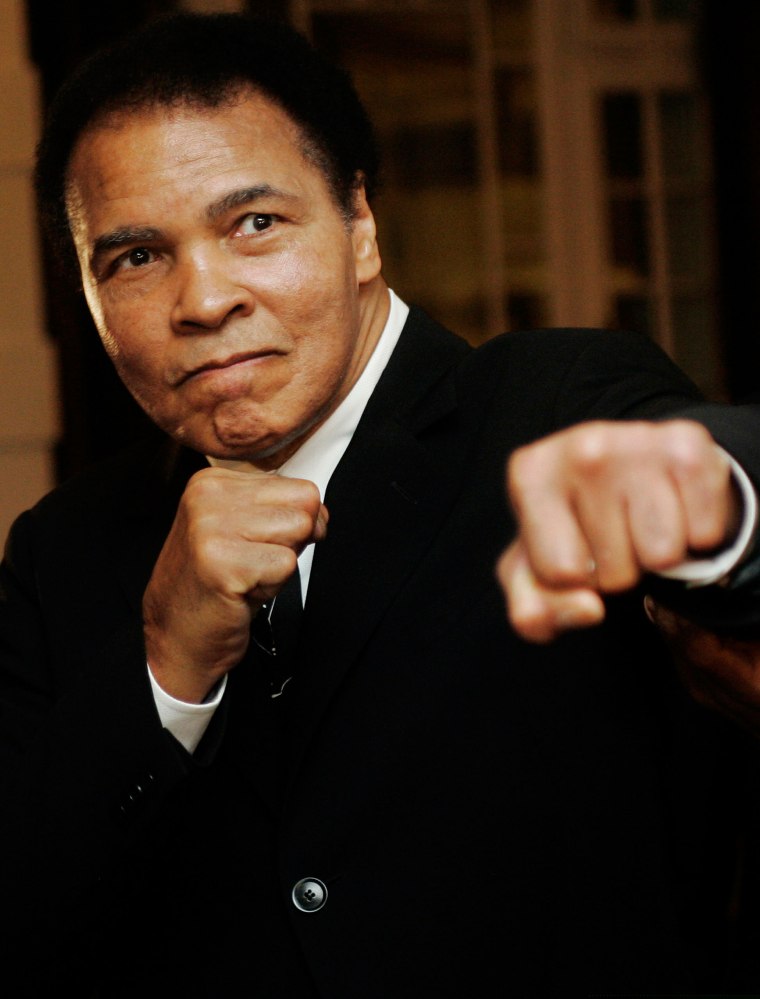

There were more medical tests, mostly inconclusive. His trembling and slurring were attributed to Parkinson's syndrome, not disease, as if no one wanted to deal with such a formidable diagnosis. The various theories of causation included exposure to toxic chemicals in his training camp in Deer Lake, Pa. Few beyond Pacheco would discuss the obvious: the devastating impact of so many traumatic blows to the head over so many years.

The joyride was over. Brown and then Ali's loyal cook, Lana Shabazz, died. Cosell renounced professional boxing in 1982 as brutal and sleazy. When Cosell died in 1995, Ali told the Associated Press: "I have been interviewed by many people, but I enjoyed interviews with Howard the best." Ali now seemed like no more than a chapter in history, a subject for "Where are they now?" features or all-time rankings of heavyweights. (He was rarely listed lower than third, and usually at No. 1.)

The comeback began in 1982, very privately. Ali was 40 and suffering through a difficult parting with Veronica when he was reunited with Yolanda Williams, a 25-year-old sales rep at Kraft working on her MBA at the University of Louisville who had had a crush on Ali since she was 5 years old. Lonnie, as Williams is known, was disturbed by his condition at their first meeting. "He stumbled on the street," she told Hauser. "He was despondent. He wasn't the Muhammad I knew."

She quit her job, moved to Los Angeles, and transferred to UCLA. And she began to take care of Ali. In 1986 they married. Lonnie became a Muslim and the full-time manager and curator of the man and the legend. She helped him take charge of his finances and reemerge as a public figure.

Their first major project together, Hauser's bestselling oral history, was published in 1991. It put Ali back on the celebrity radar. The critical and commercial success spawned more Ali-Hauser books and a procession of Ali appearances that slackened only as his stamina waned.

Five years later, with a trembling hand, he lit the torch to open the 1996 Atlanta Olympics. One of the millions of hearts touched that night belonged to Foreman, who told Stephen Brunt in the book Facing Ali, "Ali really kind of elevated himself for me when he did the torch thing. Someone has something like Parkinson's, they'll just stay in the house and hide. They'll say, 'I don't want them to see me like this.'

"I felt so proud of him. Muhammad Ali did a lot for the world when he did that. You'll never know how much he did for people who generally hide themselves. To see him do it and not be ashamed."

In 1999, Ali became the first boxer to grace a Wheaties box. In 2003, the art publisher Taschen produced a $7,500 book, a 75-pound valentine to his life and legend. In 2005, the Muhammad Ali Center opened in downtown Louisville and President George W. Bush, calling Ali the greatest boxer of all time, hung the Presidential Medal of Freedom around his neck. A year later an entertainment company, CKX, announced it had paid "$50 million for an 80 percent stake in Mr. Ali's name, image and likeness," according to The New York Times. The company also controls Elvis's image.

Hauser saw many of these moments as eroding the legacy. He was offended (as was I) by the way the 2001 movie Ali, with Will Smith in the title role, "sanitized" the man and "rounded off the rough edges" of his tumultuous journey. There was a backlash to the makeover of Ali's image, mostly in recent years from right-of-center critics who saw him as the false icon of hypocritical liberals. Even a well-known African-American academic, Gerald Early, editor of The Muhammad Ali Reader, tried to reduce his stature. He wrote: "Ali, despite all the talk of his brilliance, was not a thoughtful man. He was not conversant with ideas. Indeed, he hadn't a single idea in his head, really. What he had was the faith of a true believer … a grand public stage, an extraordinary historical moment, amazing athletic gifts, and good looks."

Such criticism provided a counterpoint to the hagiography of the movie, the Ali Center, and his corporate sponsors. The metamorphosis of Cassius Clay (brash and uneducated, yet a daring anti-establishment warrior) into the late-life Muhammad Ali (nonthreatening, passive, a wounded champion of peace and kindness) was hard to explain to a generation that had never seen him at his fiery best. It was easier to trot out a one-dimensional saint for commercial and ceremonial occasions than to teach young people about a great athlete of principle who taught the world to be proud and brave.

What is in danger of being lost in the sanitized version of Ali is the intensely American story of a black man whose journey from a boyhood in the Jim Crow South to international acclaim took him through a religious conversion, a political education and conscious decision to sacrifice comfort and wealth for his convictions.

Ali himself was rather modest in his demands on posterity. In a 1975 Playboy interview, he offered how he would like to be remembered: "As a man who never looked down on those who looked up to him and who helped as many of his people as he could … I guess I'd settle for being remembered only as a great boxing champion who became a preacher and a champion of his people. And I wouldn't even mind if folks forgot how pretty I was."

For half a century, whether or not we wanted to go, Muhammad Ali took us, Beatles and all, for a wondrous ride in which we made him a symbol of the resistance to war, of the racial struggle, of the individual standing up to establishment pressure.

Along the way he made us laugh, curse, cheer, and cry. Most important, he made us brave.

hopkinscarapt1964.blogspot.com

Source: https://time.com/muhammad-ali/

0 Response to "Black Kid Who Pulled His Pant Way Up His Waist Had a Funny Voice Who Was It"

Post a Comment